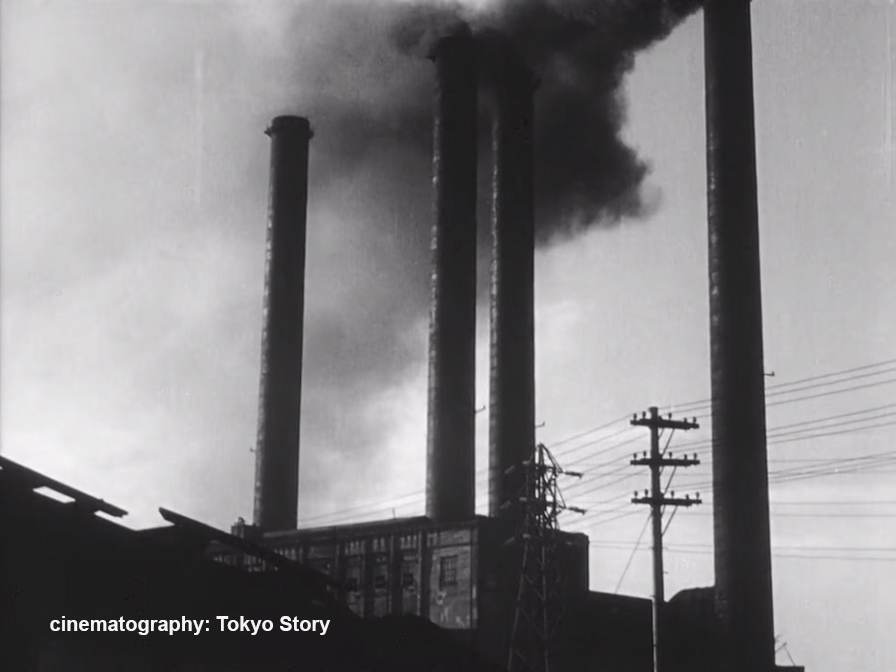

I compiled a small gallery of stills from the 1953 Yasujirō Ozu film, Tokyo Story.

I simply took screenshots when the camera stayed put on some detail or setting, free from dialogue.

These shots are simply but beautifully framed and together would not be out of place as a photobook or exhibition.

The cinematography of this film is something special. The camera moves once only, in a scene in Ueno park where the elderly couple who have made a long trip to Tokyo essentially hang out because they have nowhere to go. Their adult children are too absorbed and too busy.

Every other shot is static. The camera lingers on the simplest of things: trains passing, smoke rising from stacks, rooftops dropping down towards a harbour.

Every frame is carefully chosen, and in each the world is given freedom to move. The plot is not hauled along at every step. It emerges as one aspect of the film, slightly disengaged, unhurried, naturally, profound. We get to settle into the sights and sounds of the city as we learn about the family of characters and their stories. We see lanterns bob in a breeze and hung clothes flap dry.

By the end of the film you are comfortable in this busy 1950’s Japan. The abominable war is very recent memory and a great rush is underway to industrialise. It strains traditional rhythms of living. Children grow distant in absorbing city lives defined by work and its roles. Parents that aimed at traditional status question the value of their efforts. Now they are old, they protest at their own inconvenience.

“I don’t want to be a burden.”

Do we not resonate with this? We live in another age where each generation leapfrogs its previous, and we buy into ideals of each being both the lead character and director. And then we inevitably end up being leapfrogged ourselves. So it goes.

How many films are brave enough to let a shot linger on an entire train rumbling by, or reveal to us that the changes of life are by their nature, inevitable and disappointing. We grow up, we grow apart, we fail, disappoint, and regret. It is not so simple as spotting good guys and bad guys and expectorating justice as the plot rumbles in a straight line to a finish line. There is no checkered flag.

Kyoko:

Isn’t life disappointing?

Noriko:

Yes, it is.

The camera is normally low but sometimes peers out of windows down at a passing train, sometimes at eye level looking up at the steel infrastructure of progress. Edges of buildings and rooftops anchor compositions. Strong lighting creates a sense of depth and drama. There is an incredible consistency and realism.

Both photographic and filmic, the camera stops but elements of the scene move. This movement is often in a particular plane, such as a little group moving diagonally past a school, a group of students crossing a hallway, or a bus passing between buildings in the middle distance.

Locations are repeated, building up a familiarity and setting scenes in a contemplative mood. The same rooftops, the same harbour: but if you look closely you can see that the light has changed, and the sun has moved. However, the same line of clothes might be blowing on the line.

It is interesting to consider how these long static shots affect the pacing. If one or two were used, they might disrupt the flow, as the viewer would read a lot of significance into the act. “Why is the camera staring at this? Is it part of the plot?” But when established early on the pace becomes clear and the effect meditative. The viewer does not scramble to tie the shot into the plot. There is a careful minimalism at play, and a visual progression that could stand as an independent documentary photographic project. There is also something of Monet’s haystacks or Notre Dames paintings, of impressions of light on the same subject at different times.

Tokyo Story stills:

Cinematographer: Yūharu Atsuta

Director: Yasujirō Ozu

Writers: Kōgo Noda and Yasujirō Ozu

Released: 1953