Let the roads twist out and on

From sunken bog to sea

The blackthorns wait and long

To know which wind to free

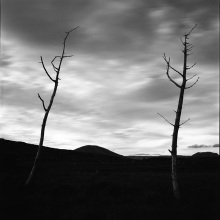

The winters here are long and dark. As the earth’s tilt pushes the northern hemisphere away from the sun’s spill, night eats into day. In one fell swoop when DST is knocked off, it gobbles all the way into the nine to five. Now you are driving home in darkness, with the wipers on, at 5pm. The landscape is concealed in black, mountains and bogland are shrouded in a quilt, and the trees give up and release their precious leaves.

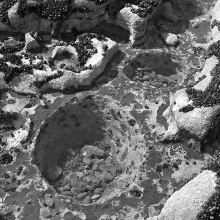

This is the western edge of an island on the western edge of Europe. The land is bruised and hacked by the Atlantic ocean, softened and scarred by the rains driven in, strewn with rock and laden with soft bog. Broad low well-worn mountains are fists of knuckles. The maamturks, the tweleve Bens, the partries. There is salt in your face, water in your shoes, and wind in your hair. You may or may not be within the disputable edges of Connemara, west of the Corrib, north of Galway, somewhere on a narrow pot-holed road that will eventually reach the sea.

The Conmaicne Mara, Conmac’s tribe of the waves, the hound son’s men of the waves…. con=hound, mac=son, mara=waves. The names go down into the bog and up into the hills. Footholds are deceptive, a shoe may be lost an ankle twisted, a hidden pool of pitch black bog water waiting to catch a misguided step.

This is the land where the wildness was unpaved for so long that gaeilge survived the centuries long rule of the English throne. It remained a foreign place, a remote place, a stubborn land that fought the bend of crops, gnawed at the hooves of livestock, flooded and sank and sloped and buckled and pitched, made you spend a generation clearing rocks out of a patch to call it a field, lrt you eke out a living on hardy potatoes from SOuth America then blackened them all and you along with them.